Turning Anger into Happiness – Here’s How to Make a Happy 2022

Contents

(Photo credit: pinterest.com)

Part 1: What is anger

Every day, we go through life experiences that directly impacts our feelings and our emotions. While feelings are conscious, emotions can be either unconscious or conscious.

Two of the most common emotions that you will experience daily are anger and happiness. The Oxford Advance Learner’s Dictionary defines anger as “the strong feeling that you have when something has happened that you think is bad and unfair”. Anger can be traced back to our ancestors’ basic survival and was honed over the course of human history. It was the emotions that prepared humans to fight, one of the options in the ‘fight, flight, or freeze’ response of the sympathetic nervous system.

(Photo credit: https://bit.ly/3p9iWiI)

(Photo credit: https://bit.ly/3p9iWiI)

As we all know, experiencing anger and acting out on it can destroy relationships as well as emotional and mental well-being. There are many famous quotes that highlight the harms of anger, such as “Speak when you are angry, and you will make the best speech you will ever regret” by Ambrose Bierce and “To be angry is to revenge the fault of others upon ourselves” by Alexander Pope (qtd. in Pepper). Thousands of years before Bierce and Pope, the Buddha himself also commented on this deep-seated human emotion, including “You will not be punished for your anger, you will be punished by your anger” and “Keeping anger in mind is like holding a hot coal with the intention of throwing it on someone else; You are the one who burns in it.” (qtd. in Payutto)

(Photo credit: pinterest.com)

Another less-known result of anger is that it can also damage one’s physical health in the long term. This is because when one is in a state of anger, stress hormones are released that can destroy neurons in areas of the brain associated with judgment and short-term memory, and weaken the immune system. This could be linked with the Buddha’s commentary on the physical state of a person to experiences anger often: “An angry person creates self-inflicted harm, for example: his appearance is wretched, his facial features are cheerless, he sleeps miserably, etc.” (qtd. in Payutto).

(Photo credit: https://bit.ly/3eqcKwD)

Anger results from a combination of three components: a trigger event, the personality traits of the individual experiencing the event, and the individual’s appraisal of the situation. Perhaps most importantly is cognitive appraisal—appraising a situation as blameworthy, unjustified, punishable, etc. The combination of these components determines if, and why, people get angry.

Part 2: What is happiness?

While not the exact opposite of anger, happiness could also be considered a state where anger does not exist. As the Buddha said, “Elimination of anger is happiness”. The Oxford Advance Learner’s Dictionary defines happiness as “the state of feeling or showing pleasure” and could be expanded to “a state of well-being that encompasses living a good life, one with a sense of meaning and deep contentment”

(Photo credit: pinterest.com)

It is safe to assume that all beings wish to exist in a state of happiness and contentment, even if it is a very difficult task and our everyday life is fraught with events that detract or distract us from that goal. As Saint Augustine said, “A man still wishes to be happy even when he so lives as to make happiness impossible” (qtd. in Pepper).

While anger destroys relationships and mental, emotional, and physical well-being, happiness can improve our physical health; feelings of positivity and fulfillment seem to benefit cardiovascular health, the immune system, inflammation levels, and blood pressure, among other things. Happiness has even been linked to a longer lifespan as well as a higher quality of life and well-being.

So where does happiness come from? Just like anger, happiness stems from trigger events, the personality traits of the individual experiencing the event, and the individual’s appraisal of the situation. Trigger events may include achievements, marital status, social relationships, life circumstances, genetic makeup, even our neighbors.

(Photo credit: pinterest.com)

(Photo credit: pinterest.com)

In life, we strive for the perfection in these trigger events because we believe that it will lead us to happiness. In the Buddha’s teachings, however, he points out an easy way to achieve happiness that does not require the pursuit of perfection in trigger events at all. Rather, he teaches us that happiness can be created within ourselves: “The disciplined mind brings happiness” (qtd. in Bomhard). Essentially, the Buddha is suggesting that by training the mind, you can literally create happy thoughts. We will look at how to train the mind further in Part 7.

(Photo credit: pinterest.com)

(Photo credit: pinterest.com)

For now, let’s explore the Buddha’s teachings on happiness.

Part 3: The Buddha’s teachings on happiness

If I ask you to picture the Buddha, you might imagine a man in a saffron-colored robe sitting crossed-legged under a tree, eyes closed, with a faint smile on his face. If I ask you to imagine Buddhist monks, you probably imagine clean-shaven men in similar saffron-colored robes, praying or chanting, with serene expressions and faint smiles, just like the Buddha. Everyone seems, apparently, to be very happy.

(Photo credit: https://wisdomquotes.com/buddha-quotes/)

(Photo credit: https://wisdomquotes.com/buddha-quotes/)

Surprisingly, being happy and serene is not the ultimate goal of Buddhism (that is nibbana or nirvana = freedom from desire or supreme happiness), although it is a byproduct of it. By following the teachings of the Buddha, you will find yourself more mindful and, as a result, less susceptible to the triggers that cause anger. The Buddha himself has said many things on anger (qtd. in Payutto):

(Photo Credit: pinterest.com)

“One should not yield to anger.”

“One must give up anger.”

“One should conquer those who are angry through loving-kindness.”

“Elimination of anger is happiness.”

“One lives happily by not hating anyone.”

“The disciplined mind brings happiness.”

The teachings of the Buddha on how to lessen anger and be more mindful can be divided into two parts: theory and practice.

Part 4: Theory

The theories of the Buddha are essentially his counsels and teachings, passed on through the thousands of years since he attained enlightenment. According to the Buddha, to be in control of our anger, we have to endeavor to preclude the arising of anger that has not yet arisen; we have to endeavor to eliminate the anger that has already arisen; we have to endeavor to cause the arising of happiness that has not yet arisen; we have to endeavor to increase and to consciously reproduce the happiness that has already arisen; and to develop them fully.

(Photo credit: pinterest.com)

(Photo credit: pinterest.com)

In daily life, we should control or manage our feelings. Whenever we encounter arousal of anger, we should reflect wisely – to think carefully, especially about possibilities – and choose good options. We should avoid being under the influence of cognitive biases.

We must try or train ourselves to think wisely. By virtue of wise reflection (or wholesome desire, the wish to do good), un-arisen anger will not arise and arisen anger will wane or disappear.

The Buddha further advised that if anger arises, one can try to control it in the following ways (qtd. in Payutto):

- To think about or paying attention to something else. If by doing this, the anger still prevails;

- To consider the harm of anger – on how it leads to destruction and suffering. If the anger still prevails;

- To conduct one’s life by not paying attention to the anger. If it still prevails;

- To reflect on the conditioned nature of anger: to hold it in awareness as object of study for increasing knowledge, rather than considering it as a personal problem. If the anger still prevails;

- To clamp down on one’s teeth and press one’s tongue to the roof of one’s mouth, making a firm determination to restrain and eliminate the anger.

(Photo credit: pinterest.com)

(Photo credit: pinterest.com)

On a tangent, the Buddha advised his followers not even to get angry with people criticizing him or his teachings, but only if they say falsehoods: “If anyone should speak in disparagement of me or my teachings, you should not be angry, resentful or upset on that account. If they falsely disparage me or my teachings, then you must explain what is incorrect and what is correct” (qtd. in Payutto).

Theories and teachings, however, can only bring us to a certain level of understanding and awareness. Therefore, the Buddha also stressed the importance of practicing meditation, which will lead us to a disciplined mind that can be a source of happiness.

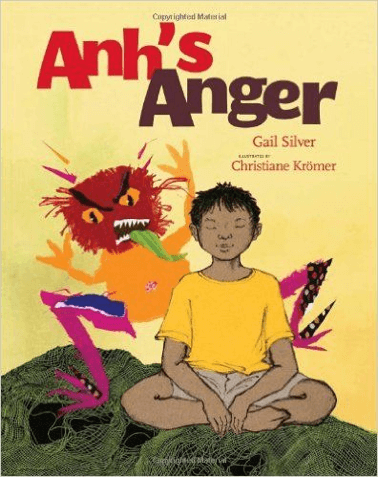

(Photo Credit: Anh’s Anger written by Gail Silver, Illustrated by Christiane Kromer )

(Photo Credit: Anh’s Anger written by Gail Silver, Illustrated by Christiane Kromer )

Part 5: Meditation, a disciplined mind, and mindfulness

Buddhism is well-known for its meditation, mantras, and rhythmic recitations. While sometimes it may seem ritualistic, these practices are ways to physically train the mind to be in a state of stillness and peace. In recent years, the western world has seemed to catch on to the benefits of meditation and countless of books and articles have been written on these millennia-old practices of South Asia.

Meditation (bhavana in Pali and Sanskrit) is as simple as it is complicated. In its simplest form, known as samatha, slowing down the breath and concentrating on the inhales and exhales will lower the body’s physiological functions, helping to achieve a state of physical calm and peace. Next is the more difficult task of lowering psychological functions, teaching the mind to become focused and attentive, chasing away random thoughts and distractions; this when insight is achieved. Through meditation, we can arrive at a state of unconcentrated distraction, or samadhi in Pali and Sanskrit.

Bodhisattva seated in meditation. Afghanistan, 2nd century CE,

Bodhisattva seated in meditation. Afghanistan, 2nd century CE,

(Photo credit: https://bit.ly/3qeByNo)

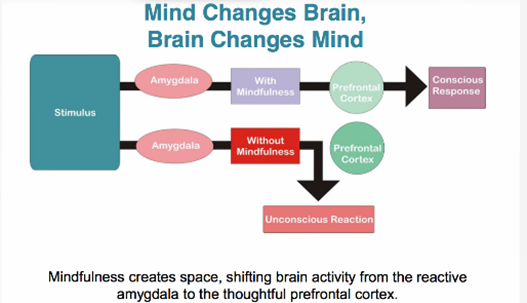

Every time that we are exposed to trigger events, our body goes into a “fight, flight, or freeze” response involuntarily. If we can take a pause between the trigger event and the response through breathing, most likely we will have better options. As mentioned above, a trigger even can sometimes lead to anger, which is part of the neurological “fight” response, but if we can steer our self away from that response through just pausing, we might not feel anger at all.

Think about this: on a very busy day, if you take a minute to take a long deep breath and then an equally long exhale, you will most likely feel calmer. The slower you breathe, the more you can control your breath, the calmer your physical body will become.

A word that has become popular recently is ‘mindfulness’, and it is what is described above. Most of the times, we live reactively and responsively. We go through life as we have always done; we react without thinking; we respond to things automatically. Mindfulness asks us to be aware of our thoughts and actions at every moment.

(Photo credit: https://bit.ly/3sBtYiF)

Mindfulness is strongly tied to meditation. It is impossible to be mindful without incorporating a daily practice of meditation in your life. We are all programmed to respond and react, but to stop, pause, and think – to be mindful – is not our second nature. But it can be cultivated.

Mindfulness makes us live in the present. It helps us to remain fully attentive to what we are experiencing or doing in each moment. Have you ever sat there and thought of something that has happened and derived some emotion out of it? That is an example of falling into the past – you are thinking of something in your brain, your mind, and not what is happening. Alternatively, if you begin to think about things that have not yet come to pass, then you are focusing on the future, on something that does not exist. To be mindful means that you are living in the present.

We will look at how to be mindful in Part 7. But first let’s talk about the science behind meditation and mindfulness.

Part 6: How we are programmed

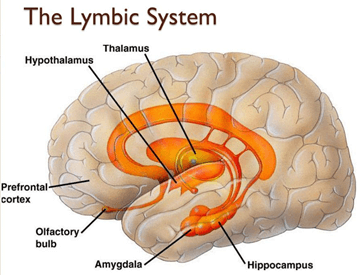

Right behind your forehead is the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system. This is the parts of your brain where actions and thoughts occur, where decisions are made, where reasoning occurs. Inside the limbic system is the amygdala, the storehouse of our emotions.

(Photo credit: https://binged.it/3mjX2HQ)

(Photo credit: https://binged.it/3mjX2HQ)

The amygdala is the part of the brain that is responsible for the fight or flight response. It is the part of us that is pure instinct, passed down to us from our ancestors through millennia of survival. It is essentially how we are programmed, how we would function if rational thought would cease to exist. While this may not sound particularly helpful, we must remember that millennia ago, our world was not like this. It was through the fight or flight responses generated through this ‘monkey brain’ that we as humans survived. But nowadays, in this world, the triggers and stimuli are different. There are so many things that affect our stress levels, and it is easy for the amygdala to come to our protection, even if we don’t need its protection.

Most of the time, our actions are determined by the activity in our prefrontal cortex. That is, when life is going as expected or as usual, we all tend to act rationally because the prefrontal cortex is in charge. When we are threatened or stressed – that is, when fear or anger is triggered – the amygdala takes over the prefrontal cortex is what is known as the ‘amygdala hijack’. It literally means what the name suggests: the emotional part of us takes over the rational part.

Try to recall the last time you were angry. Did you say or do something that you regret afterwards? Did you say or do something that wasn’t ‘the usual you’? But it was you, just the emotional, irrational part of you. And unfortunately, the emotional and irrational part of us tend to do quite a bit of damage to our relationships and our lives.

Let’s walk through a normal morning. The sound of an alarm wakes you up – that noise itself could be a stressor. You might roll over and pick up your phone to see messages – another stressor. Commuting to work could be a stressor. The hustle and bustle of the local coffeeshop could be a stressor. Within just a few hours after waking up, you have already been exposed to so many stressors! The amygdala is already on alert and active, and it would be so easy to become angry if someone does the wrong thing or something goes wrong to tip us on to the wrong side if we are not aware.

If we gave in to all triggers, if we are not mindful of our emotions, we could possibly be angry and upset all day.

On the other hand, if we are mindful, if we notice what is happening, if we can take control of our attention, we can take control back from the amygdala. Studies have shown that those who practice meditation can quiet their amygdalae and prevent this hijack. In the long run, meditation thickens the prefrontal cortex and shrinks the amygdala, mitigating the risks of future hijacks.

In this way, your brain can be trained, just like any other part of your body. Think about the heart. The heart is an organ that we can train to be stronger by doing cardiovascular exercises. The muscles in our body can become stronger with resistance training. Our vocal cords, also a muscle, can also be trained to become stronger. What seems impossible can be possible with discipline and practice. Just imagine athletes, singers, acrobats – they train so that they can perform difficult feats easily. Therefore, if we train our brains through meditation, what seems impossible – like turning anger into happiness – could be possible. It is like transforming salt water into drinking water – by process of removing salt from saltwater.

(Photo credit: https://binged.it/3mjrfql)

(Photo credit: https://binged.it/3mjrfql)

Part 7: A simple method to start meditating

In Buddhism, the goal of meditation is to reach samadhi, or ‘concentration’, which would eventually lead to the highest meditational experiences in Buddhism.

While we might not be Buddhist monks and our goal is not nirvana, we can still practice meditation to cultivate a mindfulness that will help us to be more aware of our reactions to trigger events and learn to control our emotions.

Living in this current fast-paced world with so many distractions, we are used to being aware and responsive all the time. Meditation asks us to simply sit (or stop) and let go. It does not ask us to think further, act, or respond. Being still is not something we are used to nowadays. We act and we react. Learning to stop gives us time to focus and train our minds to be less reactive and more conscious. See how to meditate in detail here.

However, the following steps are how I would in short suggest you start your meditation practice:

- Find a quiet space.

- Find a comfortable seat. Some people don’t like to sit on a hard floor, so maybe find a soft pillow. But if sitting crossed-legged is difficult for you, you can also sit on a chair.

(Photo credit: https://bit.ly/3mwVxWE)

(Photo credit: https://www.wildmind.org/posture/chair)

(Photo credit: https://www.wildmind.org/posture/chair)

- Set up a timer – maybe start at 5 or 10 minutes. Close your eyes.

- This is when your monkey brain will take over. The monkey mind is what its name suggests – the part of the mind that swings and wanders from thought to thought. It is distracted, chasing one idea after another.

- Don’t chase those thoughts. Put them aside. Imagine each thought like a cloud: you see them, and recognize them, and put them aside. This will probably be the hardest part.

- Continue to breathe, focusing on the breath and putting thoughts aside as they arise. Keep on doing this until your timer ends.

As for when and how long to meditate, it is up to you to find the best time that suits you and is conducive to peace and quiet. For me, I practice meditation every morning for thirty minutes. It is a peaceful way for me to start the day and remind myself to be mindful for the rest of the day. Some people, I know, however, like to practice meditation at night, to cleanse and destress after a long day.

Please notice that I do not ask that you feel happy all the time. We are all only humans, after all, but I ask you to be mindful. But every time you feel anger, try to be conscious about it, use the techniques you learn through meditation – such as breathing, awareness, concentration – to analyze if you really need to be angry about this issue, or is it just a passing emotion that you could let go off or turn into a positive emotion.

The first few times you meditate, more likely than not, you will not succeed. You will not be able to ‘quiet’ the mind. You will feel bored. You might fall asleep. You might find that your thoughts are louder than ever. You will, frankly, probably not feel any benefits from those 5-10 minutes except more stress or boredom.

But I ask you to continue and not give up. Like the athlete and singer analogies above, success comes from practice. It would be surprising if you are able to meditate well the first time – or even tenth. Even seasoned practitioners of meditation, or even Buddhist monks, struggle with practicing because in a way, humans have been programmed, through evolution, to always react for survival. Meditation is essentially reprogramming our brains, to make the rational part stronger than the emotional part.

Any time it becomes difficult to practice, I suggest that you remind yourself that athletes must practice, too. Achievements come from perseverance and practice, and if you don’t give up, one day you will become good at it. The first tries are the hardest, and once you find your balance, it will be rewarding.

Lastly, I would like to wish all the readers a ‘Very Happy New Year 2022’ and would like to give the Buddha’s advice from Dhammapada as another gift to ponder: “Do not run after sense pleasures and neglect the practice of meditation. If you forsake the practice of morality, concentration, and insight and get caught up in the pleasures of the world, you will come to envy those who put meditation first.”

(Photo credit: https://bit.ly/3qff3bl)

(Photo credit: https://bit.ly/3qff3bl)

******

Bibliography and Works Cited

- “Anger.” Oxford Advance Learner’s Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 2021. Web. 12 December 2021.

- “Anger”. Psychology Today, Sussex Publishers, LLC., 2021, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/anger. Accessed 12 December 2021.

- McLean, Steve. “The Tragically Hip.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, 26 Mar. 2015, Historica Canada. www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/en/article/the-tragically-hip-emc. Accessed 27 Jun. 2016.

- Bomhard, Allan R., translator. The Dhammapada. Charleston Buddhist Fellowship, 2013.

- Goleman, Daniel and Richard H. Davidson. The Science of Meditation: How to Change Your Brain, Mind and Body. Penguin Life, 2017.

- “Happiness.” Oxford Advance Learner’s Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 2021. Web. 12 December 2021.

- Ireland, Tom. “What Does Mindfulness Meditation Do to Your Brain?” Scientific American, Nature America, Inc., 12 June 2014, https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/what-does-mindfulness-meditation-do-to-your-brain/. Accessed 12 December 2021.

- Kral, Tammi R.A., et al. “Impact of short- and long-term mindfulness meditation training on amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli” NeuroImage, vol. 181, 1 November 2018, pp. 301-313. ScienceDirect, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.07.013

- Payutto, P.A. Buddhadhamma: The Laws of Nature and Their Benefits to Life. Buddhadhamma Foundation, 2017.

- Pepper, Margaret. A Dictionary of Religious Quotations. Andre Deutsch Ltd., 1989.

- Prebish, Charles S. The A-to-Z of Buddhism. Vision Books, 2014.

- “What Is Happiness?” Psychology Today, Sussex Publishers, LLC., 2021, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/happiness. Accessed 12 December 2021.

Author: Paitoon Songkaeo, Ph.D.

December 2021