Khon: The Crown Jewel of Thai Performance Arts

[cr. Buriram Rajabhat University]

In the world of Thai dramatic arts, no other forms of dance and theatre can match the scale and complexity that is Khon (โขน): a prestigious masked dance that originated during the Ayutthaya period (1350-1767).

The theatrical art of Khon combines graceful movements, combat choreography, rituals, traditional music, narration, singing, and poetry. Equally notable are the exquisite Khon masks, jewelries, and embroidered costumes, all of which require the highest skills in craftsmanship to create.

Today, Khon is considered to be Thailand’s highest form of theatrical arts, one that must be viewed at least once in a lifetime.

What is Khon?

Khon is a form of masked theatre that depicts the story of Ramakien (รามเกียรติ์), a Thai epic based on the Hindu tale of Ramayana. Actors are divided into four categories: phra (lords), nang (ladies), yak (ogres), and ling (monkeys). Though all actors were required to wear masks in ancient times, today’s phras and nangs wear a stylized form of makeup influenced by Thai mural paintings. Only performers of the yak and ling categories still adorn the elaborate masks.

Several studies suggest that the word “Khon” is derived from the Pali term “kla” or “kola”, a tuned two-faced drum that provide rhythm for dancers. Khon was initially a part of a sacred Brahman ceremony to recount the glory of Lord Vishnu. There were no audiences, as everybody participated in the ceremony. Later on, the performance became focused on the glorification of Lord Rama, the seventh avatar of Lord Vishnu whose story was recounted in the epic Ramayana.

Lord Rama (in green) riding a chariot

As Indian influences spread to Southeast Asia, the story of Ramayana became popular among the ruling class. Each country came up with their own rendition of the tale, with Thailand’s version being called Ramakien (Glory of Lord Ram). Many forms of Ramayana theatre also became popular within in the region. These included the Thai Khon, Burmese Yama Zatdaw, Cambodian Lakhon Khol, and Laotian Phra Lak Phra Lam, among others.

Prameth Boonyachai, a Khon master, believed that the art evolved from different disciplines, including Chak-Naga (ชักนาค), Krabi-Krabong (กระบี่กระบอง), and Nang Yai (หนังใหญ่). Chak-Naga is a form of theatre mentioned in a chronicle from the Ayutthaya period. The performance was said to have depicted the mythical Churning of the Milk Ocean, with actors assuming roles of divinities and demons. Krabi-Krabong, another influence on Khon, is the art of fighting with hand weapons. It is a discipline closely related to Muay Thai. Elements of Krabi-Krabong are highly visible in Khon’s combat choreography.

Nang Yai, or Grand Shadow Puppets, is another form of theatrical arts that depict the Ramakien epic. Performers manipulate large, leather puppets while dancing to the melodies of the piphat (woodwind) ensemble. Dialogues and expositions are told through narrators who stand outside the screen. This style of narrative dance and music was later adopted by the Khon theatre.

Nang Yai

In Thailand, the character of Lord Rama is closely associated with the monarchy. The Khon performance, therefore, was initially performed only for special occasions, such as royal cremations and ordinations. The dance later became popular among the public and served as a source of entertainment.

Masks and Costumes

The most unique features of Khon are the exquisite masks the performers adorn. The masks depict the four main categories of characters – phra (lords), nang (ladies), yak (ogres), and ling (monkeys) – as well as deities, hermits, beasts, and other beings. All Khon masks are considered sacred. In religious ceremonies, the masks are placed on a decorated altar and treated as representations of divinities. Performers must carry their Khon masks carefully and with respect, and must offer reverence before putting it on. It is believed that performers enter a state of trance while dancing with the masks on.

Each of the Khon masks is different in shape, color, and details, depending on each character’s physical description, rank, status, and personality. There are more than 100 types of demon masks and 40 types of monkey masks for the ensemble cast. The masks are produced by specialize craftsmen who must be knowledgeable in many disciplines of traditional craftsmanship. The creation of a single masks can take to months to complete.

Khon mask [cr. FB: Huakhon]

The glittering Khon costumes and jewelries are also exquisite to behold. The elaborate costumes are color-coded to symbolize different types of characters. For example, Lord Rama and Indra (God of War) wear green, Brahma (God of Creation) wears white, and Phra Lak (Rama’s brother) wears yellow. Traditionally, the fabric used to create the costumes is a specialized type of silk with silver and gold brocade. There are not many weavers left who still know how to produce these luxurious textiles.

The fabric is then embroidered with metallic threads and glimmering ornaments. This process requires another group of artists who are skilled in stitching. Once the clothes are ready, they are fitted onto the performers by yet another group artisans. These specialists must know exactly where to place the inner paddings and stitch the fabrics, so that the costumes do not unravel on stage.

Once the clothing is on, actors adorn themselves with jewelries. Each character possesses his or her own set of decorations, which are crafted by master goldsmiths and silversmiths. Together, the way in which the clothes are wrapped and the intricacy of the jewelries indicate the ranks and statuses of the characters.

Costume stitching [cr. www.praew.com]

Makeup artists are called upon to illustrate the faces of phra and nang dancers. These artisans must be well-studied in traditional Thai paintings, for they must be able to recreate the faces of deities depicted in temple murals onto the faces of the actors. The end result should appear as if the characters have jumped out of an illustrated scene.

Body Language

In many ways, the Khon performances of the past were more like a mimed show, as actors could not speak through the masks. The graceful body language was full of meanings and emotions. Each character group possesses their own style of choreography – phra regal, nang graceful, yak powerful, and ling energetic. As such, dancers are assigned character types early on in their trainings based on physique and motor skills.

A dance move performed by phra, nang, yak, and ling actors [cr. FB: Nitasrattanakosin]

Khon choreography takes a lifetime to master. Trainings start at a very young age, for the actors’ bodies must be conditioned like that of gymnasts. The key to executing good moves are flexibility, strength, and attention to details. The movements can be especially harrowing in scenes of war, where performers climb on top of each other to demonstrate martial prowess. Another form of specialized dance sequence is the Chuy Chai, which is performed only by highly skilled dancers to highlight grace and beauty.

Though performances today include more singing, narration, and music, the body language of Khon remains the most integral component of the art. An audience who is well-versed in reading Khon gestures can tell what the characters are saying without having to hear the dialogues.

Music, Narration, and Singing

Khon gestures are related to music, and some knowledge of the instrumental and vocal renditions allow audience members to enjoy performances on a deeper note. Khon music is played by the pi phat band: a woodwind ensemble that consists mainly of pi nai (soprano oboe), ranad ek (alto bamboo xylophone), ranad thum (bass bamboo xylophone), khong wong yai (gongs in horizontal circular frame), khong wong lek (small gongs in a horizontal circular frame), klong thad (large drums), ta-pone (two-faced tuned drums), krap (wooden clappers), and ching (small cymbals). In scenes featuring war troops, krong (large bamboo clappers) are added to provide the sound of marching footsteps. Other instruments can also be added on needed basis.

The songs used in performances are known as na phat (หน้าพาทย์) and are considered sacred. The melodies explore different emotions of the characters and are used in specified settings. For example, Paya Duen (The Walking Lord) is used when a high-ranking character is in motion and Krao Nok (The Outer Krao) is used when the monkeys are marching.

Piphat ensemble [cr. Adobe Spark]

The Khon script comprises of narrations, lyrics, and spoken dialogues. Narrations are performed by orators who speak in stylized, but non-melodic, patterns. The tones used by these orators are believed to represent the old accent of the Ayutthaya Kingdom. The narrations cover not just descriptions of natural sceneries, transports, and marching armies, but also include soliloquies, dialogues, and expressions of emotions, such as weeping and wailing. Spoken dialogues comes in the form of free verses and improvisations. Cham uad (clowns) are known to rely heavily on comedic improvisations.

Singing is an element that was adopted from Lakhon Nai, another high theatrical art that employs melodious storytelling instead of narration. Khon singing is performed by two sets of chorus, one male and one female. The chorus may sing separately or in unison. The melodic tone used is similar to that of Lakhon Nai.

Script

The Ramakien Epic and other Ramayana-derived works have existed in Thailand since antiquity. Most, however became lost during the fall of the Ayutthaya Kingdom in 1767. The Ramakien Epic was recompiled during the reign of King Rama I (1782 -1809), who commissioned for a series of Ramakien murals to be painted along the galleries of Wat Phra Kaew (Temple of the Emerald Buddha) in Bangkok.

A section of the Ramakien murals at Wat Phra Kaew [cr. Bangkok Bank SME]

The Bot Lakorn Rueng Ramakien (Theatrical Script for Ramakien) that was compiled by King Rama I is considered to be most comprehensive version of Ramakien to date. The work demonstrates unparalleled poetic beauty that can be enjoyed both as a literary masterpiece and an excellent source for theatrical productions. Khon performances today rely mostly on this body of texts. Other famous poets have also written complementary scripts for Khon throughout the years.

There are many episodes from Ramakien that depict King Rama’s heroic deeds. As the aim of the performance is to praise Lord Vishnu, Khon mostly feature episodes from Ramakien that underlines the core values of “good triumphing over evil”.

Khon and Rituals

Khon has deep roots in the Brahmanism, an ancient predecessor to Hinduism. To perform Khon, one must start by paying respect to the Khon masters. An important part of performances is the hom rong (โหมโรง) overture, which is played before the show can begin. The first song to be performed is Sathukarn (The Melody of Reverence). Any performers, musicians and dancers alike, who hear the music must stop to offer candles and incense to the masters. If they are not able to do so, then they must pay their respect by performing a wai (pressing their hands together above their heads) in remembrance of the masters. Khon masters consist not only of living and deceased teachers, but deities such as Lord Shiva, Lord Ganesh, and Lord Vishnu as well.

Once the Hom Rong is completed, a traditional prelude dance known as Berk Rong (เบิกโรง) is performed. The popular dance includes a short fighting sequence between the white monkey Hanuman, commander of Lord Rama’s army, and the black monkey Nilaphat.

The Khrob Khru (ครอบครู) ceremony is an initiation ritual for Khon dancers. To perform this rite, a ritual master will place three “masks” – a hermit mask, a Bhairava mask, and a serd (Southern Thai style crown) – on the students’ head. Khrob Khru is conducted when the students have passed their lessons and are moving on to higher levels of the art.

Khrob Khru [cr. Kanchanaburi Rajabhat University]

Wai Khru (ไหว้ครู) is another important ritual for Khon. It is an annual ceremony to pay respects to the masters. Performers use this occasion to ask forgiveness for any wrongdoings and seek the masters’ blessings. New students perform the Ram Thawai Mue dance as an initiation to the world of Khon training.

From Past to Present

Khon has gone through many renditions. The rich heritage evolved from Khon Luang (โขนหลวง) played within the royal court to Khon Klang Plang (โขนกลางแปลง), which are performed outdoors; Khon Nang Rao (โขนนั่งราว), where performers sit on a bamboo bench on the stage; Khon Na Jor (โขนหน้าจอ), which is performed in front of a screen; Khon Rong Nai (โขนโรงใน) influenced by Lakhon Nai; and Khon Chak (โขนฉาก), for which scenery and props were created. Another type of Khon called Khon Sod (โขนสด) was also invented by commoners. In this type of performance, actors lift up their masks to sing improvised lines of poetry.

Khon dancers in the past [cr. silpa-mag.com]

After World War II, Khon was almost driven to extinction, being eclipsed by Western-style entertainment. The efforts to revive Khon began under the leadership of Her Majesty Queen Sirikit, the Queen Mother (then Queen Consort), who once famously remarked that “If no one will watch Khon, then I will watch it myself”. The Queen began to regularly stage performances not only for royal guests but also the general public. She also commissioned for the production of new costumes and props. Under Her Majesty’s SUPPORT Foundation, students were granted scholarships to study various disciplines of craftsmanship, many of which are involved in the process of costume making.

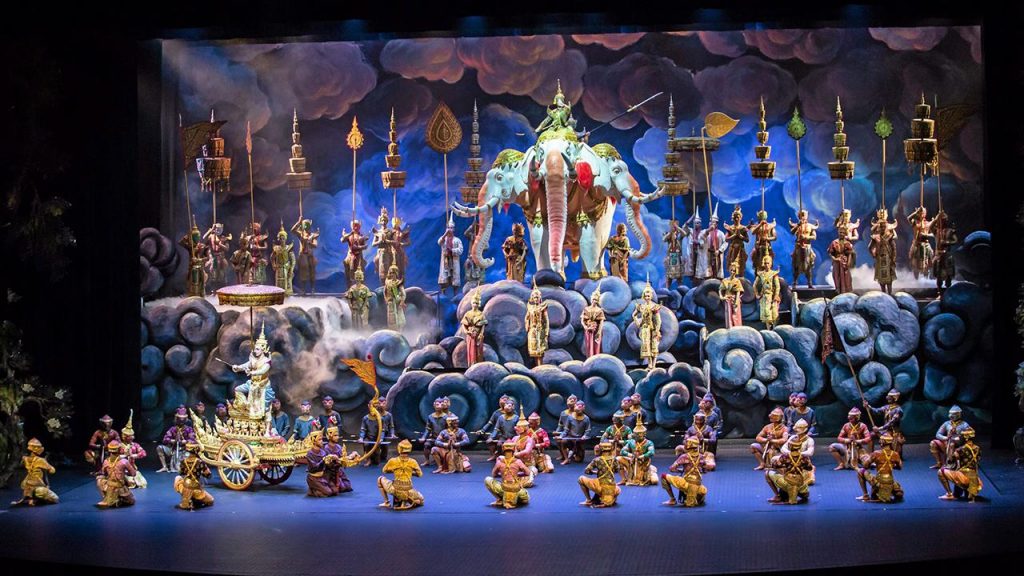

The SUPPORT Foundation finally staged its debut Khon performance in 2007. Since then, Khon traditions have risen to new heights, incorporating modern stage techniques and special effects. Today, the SUPPORT Khon Performance, commonly referred to as Khon Somdej (The Queen’s Khon), is considered the most prestigious Khon production in the country. Being a part of Her Majesty’s show is a dream for many dancers across the kingdom.

The Queen’s Khon [cr. Thairath]

The Queen’s Khon [cr. Thairath]

Through Queen Sirikit’s efforts, Khon became a thriving national heritage and source of pride for all Thai people. Different performances are organized year-round on both large and small scales, played out in theatres as well as in hotels to entertain foreign tourists. In addition, the classical art has been reinterpreted by contemporary artists like Pichet Klunchun, who stresses the dance movements and choreography in shows such as “I am a demon”, leaving his dancers topless to better show the muscles moving in the complex dances. His contribution to Khon has created some interesting responses and is credited by some for bringing a new perspective to the national heritage. In 2018, Khon was inscribed to the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

As for the audience, questions are often asked as to how they can help preserve and perpetuate the ancient art form. The answer is relatively simple: Attend Khon performances and acquire some information ahead of the show to gain deeper understanding of this cherished heritage.

Hanuman, Lord Rama’s trusted monkey soldier

*************************

Reference

Treethep, Sa-nguan. Khon Tee Sud Hang Nard Ta Gum Thai [Khon: The paragon of Thai dramatic arts]. Watthanatham Journal: Department of Cultural Promotion, vol. 55, no. 4, October-December 2016, p. 4-17. Available at http://magazine.culture.go.th/2016/4/mobile/index.html#p=5.