Triyampavai-Tripavai: The Swing Ceremony

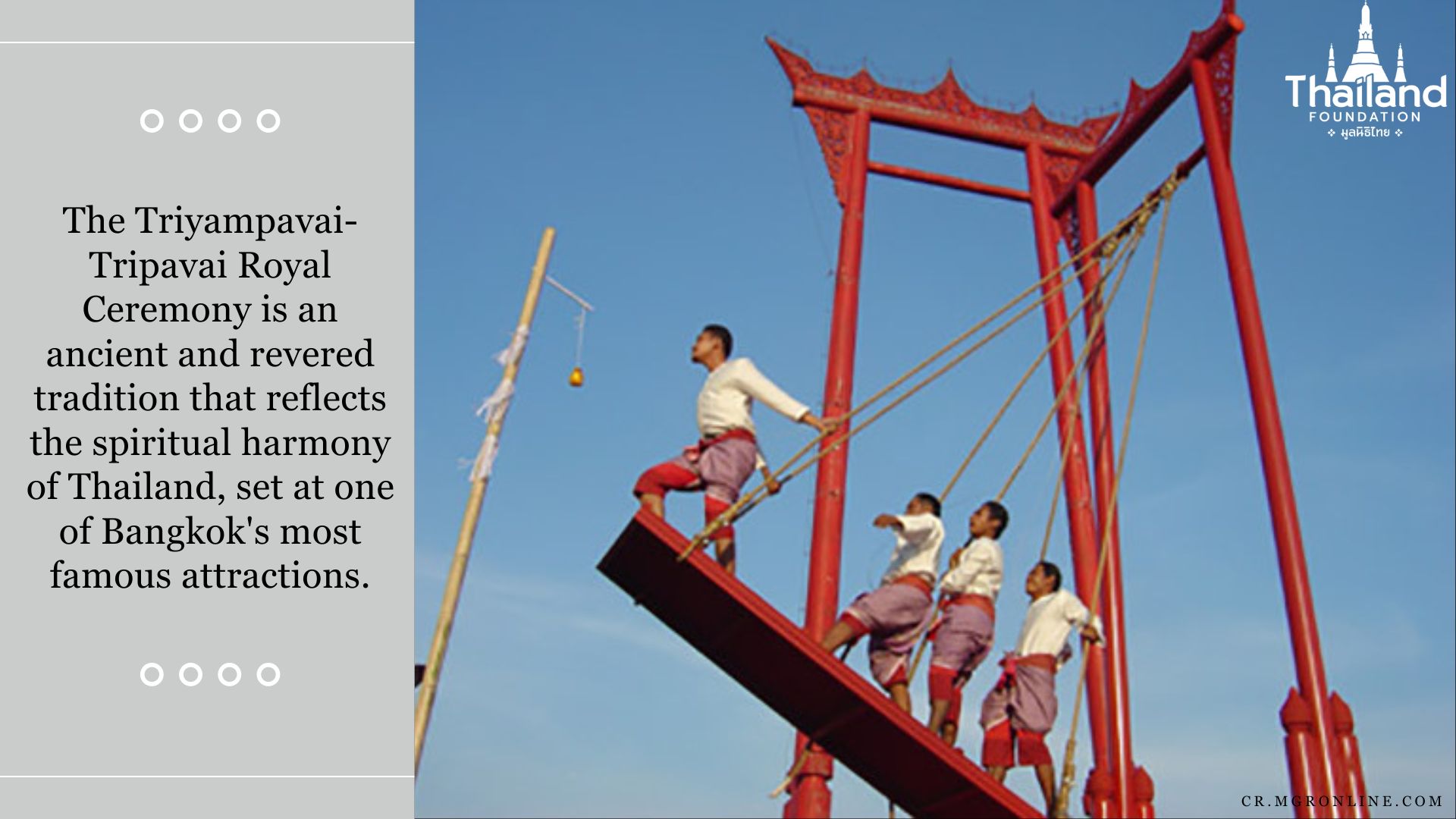

Have you ever marveled at the majestic Giant Swing in Bangkok’s Old Town and wondered what could be its significance? Many festivals and annual traditions in Thailand are deeply intertwined with Buddhism and local beliefs. For the case of the Giant Swing, its existence revolves around Brahmin-Hinduism and a sacred ancient tradition called Triyampavai-Tripavai Royal Ceremony (พระราชพิธีตรียัมปวาย-ตรีปวาย), commonly known as the Swing Ceremony.

What is the Triyampavai-Tripavai Royal Ceremony?

The “Triyampavai-Tripavai” (from the Tamil terms “Tiruvempavai” and “Tiruppavai”) marks the Thai Brahmin New Year in the Thai lunar calendar, often occurring in December or January. The ceremony is different from the Thai Solar New Year, or Songkran, which is held in April and also has ties with Brahmanism. The themes of annual festivities in Thailand are usually tied to two factors: religious beliefs and seasonal changes. The Triyampavai-Tripavai Royal Ceremony involves both components. The advent of the Thai Brahim Lunar New Year commemorates the mythological creation of Earth. On the other hand, the celebration coincides with the harvest season.

Cr. www.gotoknow.org

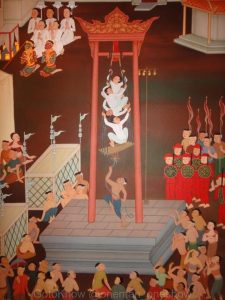

Central to the Brahmin Lunar New Year is the welcoming Lord Shiva’s visit to Earth and the praising of Lord Brahma who created the world. In the past, people would enact this belief through straddling giant swings as a part of the religious festivity. Legend has it that after Lord Brahma created and filled the world with an expansive ocean and two mountains on each side, Lord Shiva was concerned about the stability of the world. To ensure that the newly created world would last, he placed one of his feet upon it and summoned the nagas (mythical serpents) to try to rock and knock on those mountains, but the world remained intact. Lord Shiva was able to stand on the Earth without losing his balance. Delighted, all the nagas celebrated the safe and durable world and bathe joyfully in the ocean. This is how the Swing Ceremony began, where the two pillars of the Giant Swing symbolize the mountains on each side of the ocean.

Activities at the Triyampavai-Tripavai Royal Ceremony

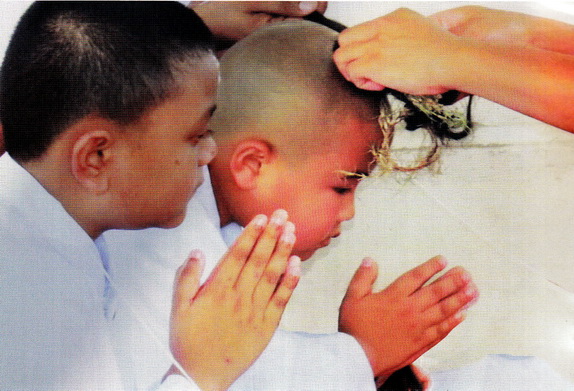

At the Devasthan Brahmin Temple (เทวสถานโบสถ์พราหมณ์) in Bangkok, the Triyampavai-Tripavai Royal Ceremony unfolds over fifteen days. The ceremony is actually the combination of two ceremonies: the Triyampavai and Tripavai Ceremonies. The “Triyampavai Ceremony” spans ten days, commemorating Lord Shiva’s descent to test the world’s stability. Following this, the “Tripavai Ceremony” takes place over the next five days, during which Lord Vishnu comes to Earth. At the end of the festivity, the brahmins (priests) also perform a hair-cutting ceremony to bless children who have come of age.

There are three crucial elements which are incorporated into the Triyampavai-Tripavai Ceremony:

1. Recitation of prayers to “open the gate of Shivalai Kailash” :This is a sacred invocation to beckon Lord Shiva from his celestial abode on Mount Kailash to bless the mortal realm.

2. Presentation of offerings to the deities: These offerings, later to be distributed to the people, will carry with them blessings and fortune.

Presentation of offerings to the deities

Cr. เทวสถาน สำหรับพระนคร โบสถ์พราหมณ์

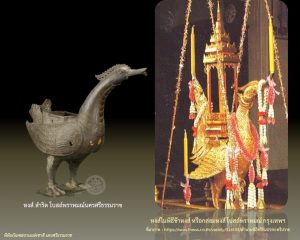

3. The “Cha Hong” (ช้าหงส์) ritual: Miniature idols of deities are bathed and onto a wooden swan that in suspended on poles with the shrine. The swan is then swung lightly as prayers are chanted in a lullaby-like melody. This ritual mimics the movement of the swan, as the divine vehicle, carrying deities back to their to their celestial palace, thereby bringing the entire ceremony to its conclusion.

The swan used in “Cha Hong” (ช้าหงส์) ritual

Cr. กรมศิลปากร

The details of the ceremony in each day are as follows:

Day 1: The court brahmins assume monastic vows for the duration of the ceremony. The Vedas are read to open the door of Shivalai Kailash and invite Lord Shiva to the world. Blessed rice and various offerings, including bananas, popped rice, oranges, cucumbers, taro, potatoes, triangular shaped sticky rice, old coconuts, and young coconuts, are offered to Lord Shiva and Lord Ganesha.

Cr. เทวสถาน สำหรับพระนคร โบสถ์พราหมณ์

Day 2: The court brahmins pray and present offerings to Lord Shiva and Lord Ganesha.

Day 3: This day is the Swing Day, but since the swing swaying is no longer practiced, it is replaced by another brahmin ceremony involving placing swing boards in holes. The court brahmins then pray and present offerings to Lord Shiva and Lord Ganesha

Day 4-5: The court brahmins pray and present offerings to Lord Shiva and Lord Ganesha.

Day 6: The swing boards are retrieved from the holes and placed in the temple where they are usually kept. The court brahmins then pray and present offerings to Lord Shiva and Lord Ganesha.

Swing boards depicting the Earth Goddess (left), Water Goddess (center), and Sun/Moon (right)

Cr. เทวสถาน สำหรับพระนคร โบสถ์พราหมณ์

Day 7-9: The court brahmins pray and present offerings to Lord Shiva and Lord Ganesha.

Day 10: During the morning, the court brahmins present offerings. Later in the day, the Vedas are read to open the door of Shivalai Krailas for a second time, but this time to invite Lord Vishnu to Earth. In the evening, the court brahmins receive sacred idols of Lord Shiva, Parvati Devi, and Lord Ganesha that are sent from the palace. At night, the court brahmins pray to Lord Shiva and Lord Ganesha, before performing the Cha Hong ritual to send off Lord Shiva. The ceremony ends with the closing of Lord Shiva’s Shrine.

Day 11: The court brahmins present offerings before visiting the palace to deliver the offerings and blessings to the king and the Royal Family. The Thai monarch is the official patron of the Triyumpavai-Tripavai Royal Ceremony. In the past, kings and royals would personally attend the ceremony. At night, the court brahmins continue with prayers. The event concludes with the closing of Lord Shiva’s shrine.

Day 12: The court brahmins present offerings in the morning. Later in the day, they receive a sacred idol of Lord Brahma sent from the palace. At night, the court brahmins pray and perform the Cha Hong ritual to send off Lord Brahma.

Day 13: In the morning, the court Brahmins present offerings and visit the palace again to deliver the offerings and blessings to the Royal Family. At night, the court brahmins pray to Lord Vishnu.

Day 14: The court brahmins present offerings in the morning. In the afternoon, preparations for the hair-cutting ceremony takes place. Nine high-ranking Buddhist monks are invited to chant Buddhist mantras. Children to undergo the hair cutting ceremony on the next day will listen to the mantras and receive blessings. At night, the court brahmins pray and sends off Lord Vishnu through the Cha Hong ritual. The event concludes with the closing of the Lord Vishnu Shrine.

Day 15: The hair-cutting ceremony is performed. The court brahmins offer alms to Buddhist monks. The ceremony concludes with a candlelight procession and the anointing of the idols. The idols are then returned to the palace.

The Swing Ceremony

Cr. ngthai.com

As previously mentioned, the “Triyampavai Ceremony,” commemorates the legend of Lord Shiva descending to ensure the world’s stability by ordering the powerful nagas to rock the mountains on both sides of the ocean, subjecting the earth to an endurance test. Thus, the most iconic aspect of the ceremony is arguably the “Swing Ceremony” where the creation myth is re-enacted.

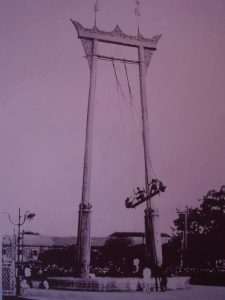

The ceremony is performed at one of Bangkok’s most iconic sites: the Giant Swing. The two poles, over 21 meters in height, symbolizes the mountains. Wooden boards attached to the Giant Swing featured images of the Earth Goddess (พระแม่ธรณี), the Water Goddess (พระแม่คงคา), the sun, and the moon, symbolizing divinities who have come to greet Lord Shiva. The swing board was manipulated by the naliwan (นาลิวัน), a group of men adorned with naga headdresses. Ascending the board, the naliwan enacted the mythical endurance test of the Earth swing the board high into the air. The goal was to swing far enough for the naliwan positioned at the front of board to bite and snatch a money purse that was hung from a tall bamboo pole in front of the Giant Swing. Also placed before the pole is the khan sakhorn, (ขันสาคร), a giant metallic bowl of water depicting the ocean. “Phraya Yuen Chingcha” (พระยายืนชิงช้า), or “Lord Who Stands the Swing”, assumed the role of Lord Shiva and presided over the ceremony. At the end of the ceremony the naliwan perform a dance using animal horns to scoop holy water from the khan sakhon to sprinkle onto the crowd.

As a noteworthy aside,“naliwan” translates to “four men,” signifying the four performers on each swing board. The ceremony requires three swing boards, totaling 12 naliwan performers. Meanwhile, the person who originally assumed the role of Phraya Yuen Chingcha (พระยายืนชิงช้า) was Chao Phraya Phonthep (เจ้าพระยาพลเทพ), the head of Krom Na (กรมนา), a role akin to the modern-day minister of agriculture. Later, it was replaced by a senior civil servant of the Phanthong rank (ยศพานทอง), who annually takes turns presiding over the ceremony.

The Swing Ceremony was a spectacular site to behold, with huge crowds gathering to celebrate and witness the daring feat. Yet, the ceremony was very costly and dangerous. Some naliwans were said to have lost their lives during the process. Thus, the practice was stopped in 1934 during the reign of King Rama VII. Though it has been discontinued, stories of the Swing Ceremony are still passed on through generations of Thais and an impressive structure – the Giant Swing – still stands as its monument.

History of the Triyampavai-Tripavai Royal Ceremony

Brahmanism-Hinduism, while not one of Thailand’s largest religions, exerts a profound influence on the Thai society through enduring centuries-old traditions. This religion’s early entry into Thailand was facilitated by the historical ties between Thailand and South India. The ancient text Legend of the Brahmins of Nakhon Si Thammarat (ตำนานพราหมณ์เมืองนครศรีธรรมราช) traces the roots of Brahmins in Thailand to the Tamil Brahmins from Southern India traveling to the areas that is now Southern Thailand with the aim of spreading Brahmanism to a new region.

Devasthan (Brahmin Shrines), located at Nakhon Si Thammarat

Cr. library.wu.ac.th

These Tamil Brahmins were Shaivites who worshipped Lord Shiva as the Supreme Divinity and are assumed to have brought elements of Triyampavai-Tripavai to Thailand and integrate them with local practices, such as local swinging rituals. One of the first mentions of the ceremony occurs in the Sukhothai period (1238-1438) from to the text Nang Noppamas (หนังสือนางนพมาศ). As documented in this literary piece, the Triyampavai and Tripavai Ceremonies were observed as December holidays. People gathered in front of the royal temple to witness the swing performance and the procession of Shiva and Vishnu, presided over by the Kings of Sukhothai.

Idols of Lord Vishnu (left), Lord Brahma (center), and Lord Shiva (right)

Idols of Lord Vishnu (left), Lord Brahma (center), and Lord Shiva (right)

Cr. Tayud Mongkolrat

The Ayutthaya period (1351–1767) saw, in the Three Seal Laws (หนังสือกฎหมายตราสามดวง) and the Testimony of the People of the Old Capital (หนังสือคำให้การชาวกรุงเก่า), a distinctive ceremony involving brahmins balancing on the swing board to grab a bag of money hung from a pole in front of the Swing. The swing board used was buried afterward. According to the Legend of the Brahmins of Nakhon Si Thammarat (ตำนานพราหมณ์เมืองนครศรีธรรมราช) a group of South Indian Brahmins, en route to offer royal tribute to King Narai the Great (1656 to 1688) of Ayutthaya, encountered a monsoon. Unable to reach Ayutthaya, they settled in Nakhon Si Thammarat Province. Recognizing their wisdom, the ruler of Nakhon Si Thammarat, a large city and former capital, appointed Brahmins as advisers, employing Dhammasat (ตำราพระธรรมศาสตร์) and the Laws of Manu (กฎหมายพระมนู) for governance.

Statue of Lord Shiva from the Ayutthaya Period

Cr. Hindu Meeting (Fan Page)

At the start of the Rattanakosin period (1782– Present), King Rama I commissioned the building of a Royal Brahmin Temple known as the Devasthan in 1784, followed by the iconic Giant Swing in 1786. These moments in history stand as testaments to their integral role of Brahmin-Hindu influences in Thai culture. The temple complex comprises the Lord Shiva Shrine, the Lord Ganesha Shrine, the Lord Vishnu Shrine, and the Vedas Hall, which is a ceremonial chamber doubling as a library housing an extensive collection of works on Brahmin literature, rituals, astrology, and traditions.

The Devasthan in Bangkok keeps two Shivalingas, a rarity in Brahmin temples where typically only one Shivalinga is housed. This distinct attribute is believed to have been inspired from Ramsewaram Temple in Tamil Nadu, renowned for having two Shivalingas. The presence of both a shrine dedicated to Lord Shiva and Lord Vishnu also demonstrate a connection with another famous temple from Tamil Nadu: the Chidambaram Nataraja Temple. Thus the influences from South Indian are evident in the unique characteristics of the Bangkok Devasthan.

Devasthan in Bangkok

Cr. www.thailibrary.in.th

King Rama I also brought the brahmins from Phatthalung and Nakhon Si Thammarat to Bangkok. These brahmins became the court brahmins who bear a noble responsibility of safeguarding the Vedas and performing religious rituals for the state. One of their many important duties is to perform the Triyumpavai-Tripavai Royal Ceremony. Later in 1888, King Rama V wrote a book called The Twelve Months of Royal Ceremony (พระราชพิธีสิบสองเดือน). The book mentioned that the time of the Ceremony was moved to January instead of December when the water level had just receded leaving the roads muddy and inconvenient for the ceremony.

Cr. thairath

Cr. thairath

The practice of the Swing Ceremony was stopped in 1934 during the reign of King Rama VII due to its high risk and cost. Yet, the court brahmins was allowed to continue performing the prayer and Cha Hong rituals exclusively every year among themselves at the Devasthan Brahmin Temple. Many years later, King Rama IX directed the restoration of the ceremony as a public event, bringing back all ceremonial elements except for the practice of having the Naliwan stand on the swing boards.

Today, the Devasthan Brahmin Temple is home to court brahmins from only seven Brahmin families. Each brahmin holds a prestigious position as royal officials, directly reporting to the Royal Ceremonial Division. To become a Brahmin, one must descend from a Brahmin lineage, in other words, be a son of a Brahmin. The current Chief of the Court Brahmins is Phra Maharaja Guru Bidhi Sri Visudhigun Chawin Ransibrahmanakul, who is also the leader of Brahmanism-Hinduism in Thailand.

Values and Significance

In the vast landscape of the Thai festivities, the Triyampavai-Tripavai Royal Ceremony stands as a testament to the interwoven fabric of history, morality, life transitions, and political symbolism. The ceremony mirrors the enduring coexistence of Brahmin-Hindu beliefs and Buddhism in the Thai society. The sound of Hindu mantras intermixing with praying Buddhist monks and alms giving ritual reflect a harmonious blend between the two faiths.

As an auspicious welcoming of the New Year, the Swing Ceremony reminds people to be grateful for the world’s generosity and the bountiful land that sustains all lives on it. Symbolically, it marks the transition from childhood to adolescence, encapsulated in the hair-cutting ceremony—a Brahmin tradition representing honor and growth.

Beneath the surface, the ceremony preaches the value of prudence, mirrored in Lord Shiva’s meticulous verification of the world’s stability. He ordered the Nagas to rock the mountains not once but thrice, thus the three swing boards in the ceremony. In life and governance alike, this echoes the importance of caution and thoughtfulness.

On the state level, the Triyampavai-Tripavai Royal Ceremony becomes a way for the Kings of Thailand to spiritually serve their subjects. A large part of the Thai population practices agriculture for a living. Thus, in it is traditionally crucial for the Thai kings to conduct rituals that secure a successful harvest for his people. The Triyampavai-Tripavai Royal Ceremony is intrinsically linked to another ritual: the Royal Ploughing Ceremony (พระราชพิธีจรดพระนังคัลแรกนาขวัญ). The Royal Ploughing Ceremony is conducted at the beginning of the planting season to raise hope and morale for farmers. In this ceremony, the king beckons the gods to bless his people with successful crops. Once the crops are harvested, the Triyampavai-Tripavai Royal Ceremony comes into play. Here, on the king’s behest, the court brahmins present the harvest as offerings to the Gods to thank them for their blessings.

The Royal Ploughing Ceremony

Cr. news.mthai.com

Conclusion

An old belief has it that, wherever the Triyampavai-Tripavai Ceremony is performed, prosperity and unity shall reign, and resilience shall prevail over adversity. Perhaps, there is a deeper meaning behind this thinking. Through the eras, the Triyampavai-Tripavai Royal Ceremony has endured as a living remnant from the ancient past. Its history, myth, and rituals are beautiful reflections of Thai values and wisdom. The legend of creation reminds people to be grateful of what the Earth provides as well as to live with prudence and mindfulness. Meanwhile, the elements of the celebration are emblematic of the Thai people’s openness towards diverse faiths and cultures, seamlessly integrating Brahmin beliefs with Buddhist and local influences. From past to present, from monarchs to commoners, the ceremony speaks of the enduring spirit that binds the Thai people together—a union between tradition and progress.

The story of “Triyampavai-Tripavai Royal Ceremony” is one of the classical aspects of Thai culture and heritage. The ceremony reflects a harmonious blend between beliefs, which is characteristic to the Thai value of openness. The lessons from this ancient rite also provide attendees with wisdom and guidance in living. Join us in exploring more stories of Thailand and the Thai people, as we take you on a journey to discover Thainess.

Sources

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PIjJ8OjXYaY

- http://www.devasthan.org/ceremony_main.html

- http://tinyurl.com/5n83n4h4

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fIITT77LuF8&t=69s&pp=ygUV4Lie4Lij4Liy4Lir4Lih4LiT4LmM

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hiP99VFs-_s&pp=ygUV4Lie4Lij4Liy4Lir4Lih4LiT4LmM

- http://www.devasthan.org/history_html

- http://www.devasthan.org/history_html

- https://www.finearts.go.th/uploads/tinymce/source/1/km/Old_Photo_55-3.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LFTzU183wrc

Author: Soonyata Mianlamai

Editor: Tayud Mongkolrat

30 January 2024