Tum Khwan Kaow: The Traditional Rice-Beckoning Ceremony of Thai Farmers

Tum Kwan Khao in Surat Thani Province (cr. Ministry of Culture)

¨Dear Mae Phosop, the enlightened Goddess of Prosperity and Mother of Rice, we beckon thee to descend upon the paddies and accept our offerings of food to appease your appetite for sweet, sour, and savory, for all who live here welcome the Mother. Please eat and bless us with a fine harvest, free from disaster. Please fill our wicker baskets with your rice. Please allow the rice we are growing to blossom like galangals across the paddy fields.”

One can hear farmers sing this verse of the Harvest Song, resonating across the fields as farmers assemble offerings on Friday evening following the end of the Buddhist Lent, which is in October. This time coincides with when the provinces of Central Thailand experience a seasonal flooding of rice paddies. The deposit of silt rejuvenates rice stalks and creates a lush green as new panicles begin to form. As they ripen, the stalks begin to separate and spread outwards in what Thai farmers refer to as hang platoo, literally “mackerel tail.” The Rice-Beckoning Ceremony, known in Thai as Tum Khwan Kaow, commences in many provinces.

The Rice-Beckoning Ceremony is a tradition held across Thailand. How frequently and when exactly depend on the region. In Central and Southern Thailand, the ceremony typically happens a few times throughout the year: it happens first during a period known as “panicle initiation,” a term that refers to the end of the vegetative state of rice; then, the ceremony is carried out again during harvest, and for the third and final time when the rice is being transferred into storage huts. (More on the ceremonies of Central Thailand will be discussed below.) In Northern and Northeastern Thailand, on the contrary, the Rice-Beckoning Ceremony is conducted only when the rice is being transferred into the storage huts. In other words, the only time every region in Thailand overlappingly performs the Ceremony is during the storage stage.

How has this festival come about? You may wonder. To understand this, one must understand that Thai farmers believe that rice paddies are akin to the belly of Mae Phosop. They believe that by offering sweet and sour foods – as if to appease a truly pregnant woman – they would be blessed with a “pregnancy” that flourishes, yielding an abundant harvest.

Mae Phosop, the Mother Goddess of Rice (Ministry of Culture)

The organization and performance of the ceremony are complex and intricate. Typically, a female leader – typically the farm owner or his wife – prepares objects of worship for Mae Phosop. The objects she must prepare are many and include: batplee, an ornament made from banana leaves and decorated with marigolds; classic desserts, such as kanom tom daeng, kanom tom khaow, and kanom huu chang; a small kathong, a banana leaf vessel that carries these desserts and floats them down a river; as well as other components of the krathong, including objects that she will need to communicate with Mae Phosop; sweet and sour foods; a star-shaped bamboo ornament called shalaew; a wicker basket; a boiled egg; freshly-made rice balls; bananas; oranges; sugar cane; betel leaves; tamarind; and salt. She also brings with her a mirror, a comb, powder, a scented water, a firm branch or twig, a sarong, a paper flag, and a ball of thread that she and the villagers believe to be holy, blessed by Buddhist monks.

Offerings for Mae Phosop (cr. bangkokbiznews)

On a boat, she enters the flooded paddies, searching for the thickest lot of rice stalks, which are a sign of strength and vitality. When she finds it, she begins to assemble the objects that she has brought, making those rice stalks an important site for the ceremony. She plants the shalaew into the field using the branch or twig, then attaches the flag, basket, and mirror. Next, she gathers together rice stalks and ties the holy thread around them to form a bundle, before beginning to “dress up” the site by draping the sarong over the rice bundle, gently combing it, sprinkling scented water over it, and powdering it, while speaking to Mae Phosop in soft, sweet tones or singing a hymn, such as the one at the beginning of this article.

Traditional scriptures on rice farming state, “the Mother is easily frightened, timid and shy. To question or to defame her will set her on her way.” Worshippers fear that a disorganized or hasty organization of this ceremony could cause the goddess to seek a new settlement, taking away the prosperity with her, in which case barrenness, drought, and starvation would come upon the region.

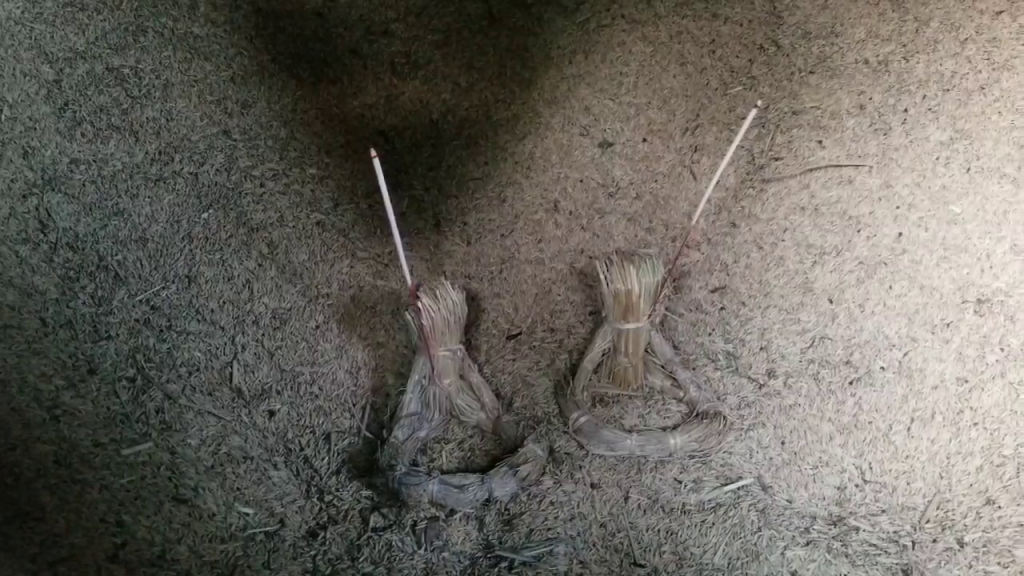

The “Tapuk” Doll

A doll – sometimes nameless, sometimes known as the “tapuk doll,” is an essential part of the Rice-Beckoning Ceremony in many regions, when the storage of the rice begins. In Ayutthaya (Central Thailand) after the rice is stored in the granaries, a female leader will go to the fields to receive blessings from Mae Phosop on Friday before dawn. There, she will be with the rice stubbles in the paddies, taking a few ears of rice and tying them together to create an embodiment of Mae Phosop. In Korat (Northeastern Thailand), this figure also appears and is known as a tapuk doll (while there appears to be name for it in Central Thailand).

The tapuk doll will be wrapped in a tricolor flag and secured to the ground with another flag. The batpalee, krathong, and offerings will be placed around it before the participants will begin chanting verses of traditional songs to welcome the Mother of Rice back to the paddies, such as this verse: ¨Mae Phosop, Enlightened Goddess of Prosperity, bring back thy glorious blessings into the sanctity of our home, away from the reach of vermin, the heat of fires, to stay in our shelter and raise thy kin.”

Tapuk Dolls (cr. Komchadluek)

The tapuk doll is then taken from the ground and taken to the threshing area where it will be placed on the bundles of rice. This would mark the completion of the first round of this part of the ceremony, before more ceremonial practices that serve as permissions to begin threshing the rice take place.

Before the rice can be threshed, the threshing area must be blessed using more colored flags and offerings in the form of jewelry and clothing for Mae Phosop. Krathong filled with nourishment will be used to line the edges of the rice stacks decorated with flags, and the area will be sprinkled in scented water before villagers thank Mae Phosop for her presence and request for her food to be fed to their families after the incense burns out. This concludes the Rice-Beckoning Ceremony for most, and farmers are allowed to begin threshing rice.

According to tradition, rice should be taken into storage on the Tuesday following the Rice-Beckoning Ceremony. For places that conduct the ceremony more frequently, farmers can take a small container of rice from the threshed pile and conduct a final ceremony with a small assortment of offerings. The farmers will briefly chant the verses of the song to re-welcome Mae Phosop back to receive more nourishment, wishing for her to continue blessing them with unlimited surpluses. The tapuk doll, offerings, and the container of rice will then be placed inside the rice hut. When the rice needs to be sold in the ninth month of the lunar calendar, farmers will conduct an opening ceremony where the rice will be shoveled into a container and permission will be requested from the goddess to sell the rice. Farmers will make a wish at the ceremony for their supplies to never dwindle, praying for there to always be rice in the huts.

Modern Changes in the Tradition

As technology changes agriculture, creating a system where harvest comes closer to a guarantee, traditions such as the Rice-Beckoning Ceremony have changed. The ceremonious aspect of rice farming is no longer as prevalent. Whereas rice could be harvested only once a year, naturally, farmers can now harvest rice up to four times a year now, using the ¨prang farming technique” and irrigation systems under the auspices of royal patronage. There is no longer a need to rely on predictions of rainfall, no longer a need to think about how natural rainfall affects when panicles will form, or when harvest will be possible, as the flood waters drain. Harvest certainties are more common. Prayers have been shortened.

Nevertheless, Mae Phosop is still greatly revered. Many groups still pay regular homage to her. However, many of those who still wish to organize a ceremony for Mae Phosop will instead aggregate rice from their respective fields to celebrate the harvest, instead of conducting the ceremony individually now.

In some communities, which have shifted away from farming as a way of life, the Rice-Beckoning Ceremony has also instead been incorporated into annual temple festivals, and more for the sake of performance. Temples such as Wat Siri Wattanaram, Wat Kwaeng Bang Rom, Wat Wang Krot, and Wat Taling Chan, which host festivals in the first week of March annually hold performances and demonstrations of the ceremony, mostly to preserve tradition and raise awareness for tourists. Not only do these demonstrations help preserve tradition, but they also act as a source of hope and motivation for farmers in times of hardship – which, despite technologies being available, surely still exist.

(cr. Ministry of Culture)

References

Sujachaya, Sudara, “ [สู่ขวัญข้าวสู่ขวัญชาวนา].” Watthanatham Journal: Department of Cultural Promotion, yr. 51, no. 2, January – March. 2013, pp. 52 – 56. Retrieved April 1, 2021. Link:

http://magazine.culture.go.th/2012/2/files/assets/basic-html/index.html#page55